Thinking about maths

April 2023

When studying mathematics at Oxford, I spent more time questioning how I should be thinking about the maths than actually thinking about the maths. The question of what I should be doing in my mind to understand a mathematical concept fascinated me.

Much of this contemplation stemmed from me failing to grasp how to learn certain mathematical topics. (I’m mainly talking about pure maths, particularly Analysis and Algebra, for those of you that are familiar with university syllabuses.) I would read the lecture notes, but have no idea how to translate the symbols in the theorems and proofs written on the page into something my mind a) understood, b) could remember and most importantly, c) link to other parts of the course.

I never really reached a useful conclusion on this. By the end of second year, I decided that my degree would go a lot better if I replaced trying to work out how to think about maths with actually thinking about maths. So despite focusing on pure courses up until then, I made the bold choice to switch to solely applied courses1.

Although understanding how best to think about maths initially had a practical outcome, namely succeeding in my degree, I still find myself mulling over such ideas nearly two years after graduating. So, it was much to my delight when I recently stumbled upon a blog post by Taimur Abdaal, who studied Maths & Statistics at Oxford.

In the post, he recounts how his friend described having a picture in his head to understand and remember a theorem and its proof; a picture with no mathematical symbols. Taimur states ‘I realised I’d been thinking about maths completely wrong my whole life.’, and that ‘This blew my mind.’.

It blew my mind too! (Unfortunately, 5 years after I took the Analysis course being described.)

What blew my mind so much was that I am very aware that I like to think about things visually, so the fact I never even considered that mental pictures of theorems and proofs could be constructed baffled me. Furthermore, the fact we’re not taught the possibility or potential for mental pictures of mathematics befuddled me even more.

To no exaggeration, I felt like I had no idea what was going on in Analysis. I rote-learned the definitions and theorems (to the point that I can still recite some of them to this day). However, I couldn’t explain the actual concepts to you. I had no grasp over how the symbols I recited for the definition of a convergent sequence described it as convergent, for example. I can now though, now that I know to think about it in terms of pictures.

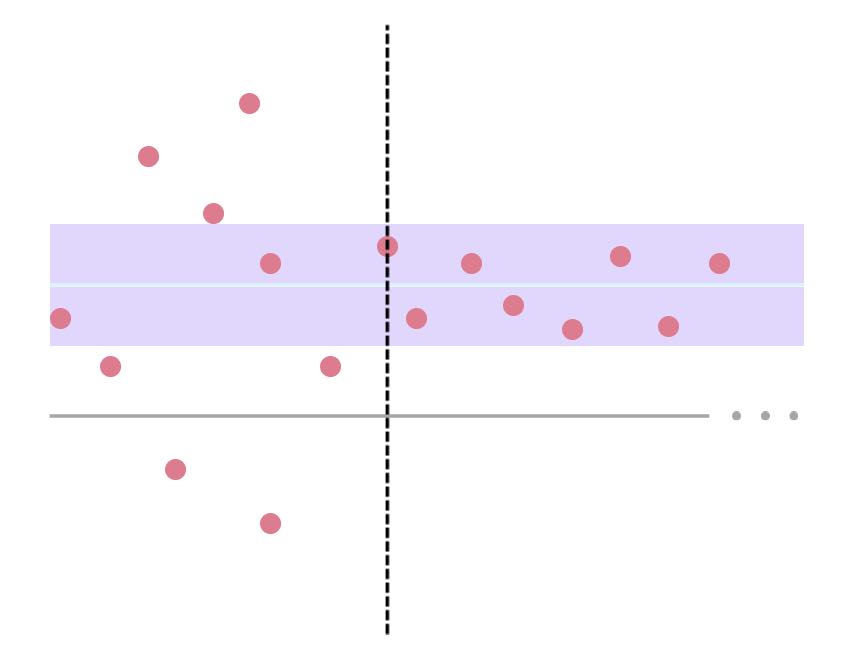

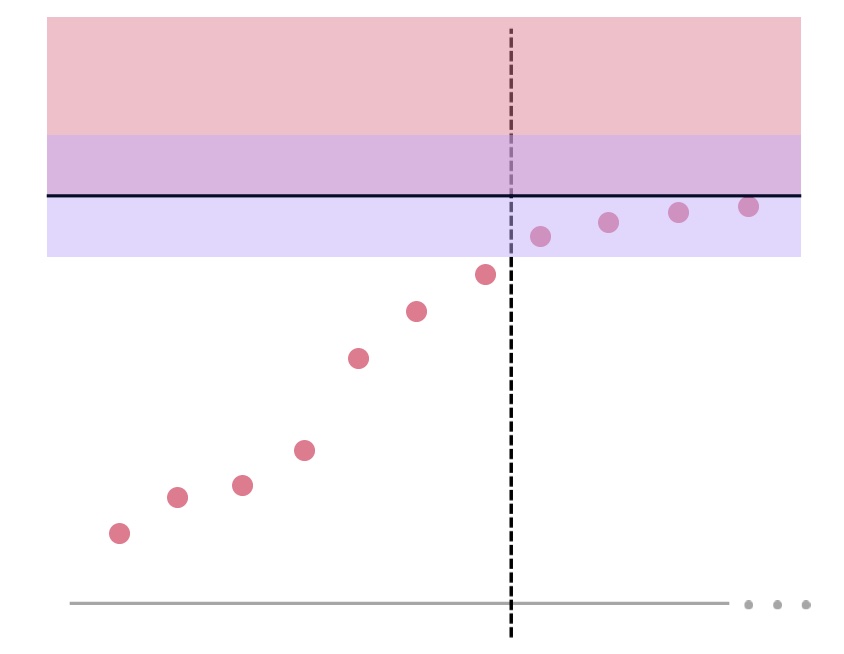

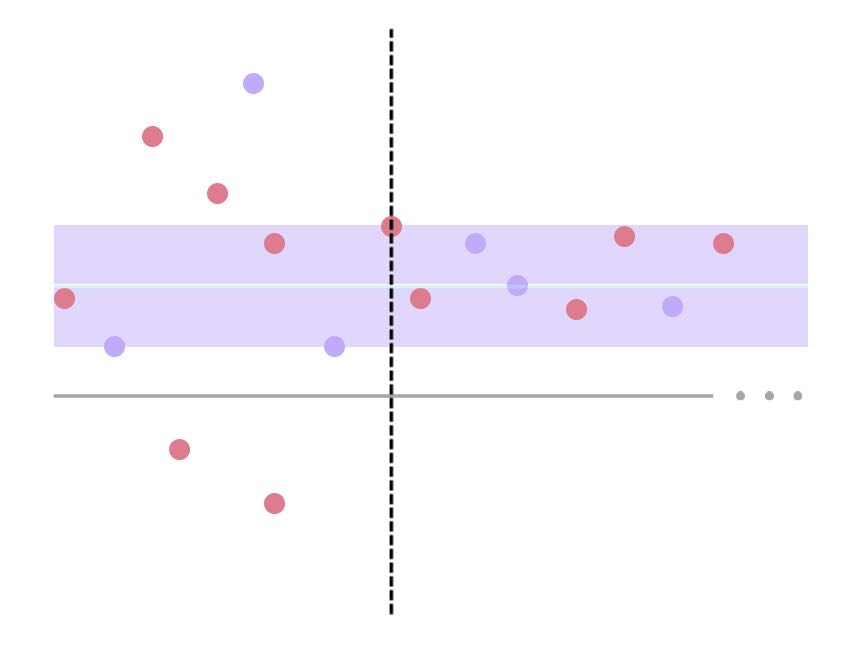

I got so excited by the idea of creating pictures to understand theorems and proofs that I decided to attempt to condense much of the Analysis 1: Sequences and Series course into pictures.

Yes, you read that correctly! I sat in a cafe for an afternoon translating the lecture notes into a series (no pun intended) of diagrams, in which symbols were banned; theorems and their proofs contained in a diagram.

Here are a few of them, accompanied with non-symbol explanations. Please read them in order. (They’d probably make more sense in video format - maybe a project for the future!)

When described with diagrams, these theorems seem almost obvious!

Is this gap in teaching (only lecturing the content, not how to think about the content) because the lecturers assume that we have this skill of turning symbols into mental representations when we arrive at university? Or are they thinking about it differently? Even more, could it be the case that they do not ever consider how they think about maths, and therefore don’t even realise it would be helpful for us to know? (My designing the way we think post delves into these questions a little further, in case they spark your interest.)

If, alongside being presented with a definition or theorem, we were told how to think about the definition or theorem, I believe my experience of mathematics at university would have been entirely different. Instead of spending hours working out how to memorise a bunch of symbols, and then attempting to answer questions by fumbling over inequality manipulations or muddling statements of theorems together, I could have practised thinking like professional mathematicians do.

Of course, it could be the case that different mathematicians think about the same theorems very differently. Are some thinking methods more effective than others? Could we combine different techniques to give ourselves a multitude of ways of thinking about a theorem? Whatever the answers to these questions, being presented with them alongside the course content would have been degree-changing2.

If, like me, you’ve been puzzled by how best to think about mathematical concepts, I’d love to hear from you! Or, if seeing the whole collection of my Analysis 1 diagrams with (or without) explanations would be useful, let me know! :)

1In case you’re wondering, despite there being many prerequisite courses to learn on top of the third year modules, this turned out to be a very wise choice for both my grades and enjoyment!

2Life-changing, but for the degree.